Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/oh/

Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/oh/

Lesson Plan

Microbes - They're Everywhere!

Grade Level

Purpose

Students will explore the varied roles that microorganisms play in the world as well as different methods for controlling their growth. Activities include using a dichotomous key to identify waterborne diseases, comparing effectiveness of handwashing techniques, reading fictional and factual excerpts about microbes, and experimenting with the growth of microorganisms on potato slices. Grades 6-8

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

- Cups of water, 1 per student

- Ammonia or lye (can be purchased as lye from the grocery store)

- Phenolphthalein (common acid-base indicator available from lab supply companies)

- Eye dropper

Activity 1: What is My Diagnosis?

- Symptoms Cards

- Waterborne Disease Analysis Key, 1 per student

Activity 2: A Germ of Truth

- Are you Petri-fied of Germs? article

- Cooking spray or vegetable oil

- Cinnamon

- Soap

- Paper towels

- Warm faucet water

- Cold faucet water

- A Germ of Truth handout

Activity 3: Cultivating an Understanding of Microbes

- 4 potatoes—washed, peeled, sliced into 1/4” rounds, and microwaved for 1-2 minutes

- Plastic resealable sandwich bags, 2 per group

- Permanent markers

- Soap and water

- Hand sanitizer

Vocabulary

bacteria: a group of single-celled living things that cannot be seen without a microscope that reproduce rapidly and sometimes cause diseases

fungus: any species in a large group of spore-producing organisms that may be one- or multi-celled and feed on organic matter; examples include yeast, molds, and mushrooms

germ: a microorganism causing disease

microbiome: a community of microorganisms that inhabit a particular environment and especially the collection of microorganisms living in or on the human body

protozoan: a single-celled organism (as an amoeba or paramecium) that is a protist and is capable of movement

virus: a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism

Did You Know?

- Most microbes do not cause disease, and some are essential for good health.1

- The human microbiome (all of our microbes’ genes) can be considered a counterpart to the human genome (all of our genes).1

- The genes in our microbiome outnumber the genes in our genome by about 100 to 1.1

Background Agricultural Connections

School is in session and there is excitement in the air—or are those germs?! Classrooms everywhere are full of students and the numerous microorganisms that all people carry. Highlighting the microscopic world of germs and teaching good hygiene practices will help keep students healthy all year long.

Microorganisms are ubiquitous—that means they are everywhere—and are generally invisible to the naked eye. While microorganimsms may live everywhere, most are harmless. It’s the few malicious, pathogenic, and contagious microbes, generally called germs, that require intervention to avoid illness.

Despite the fact that you can’t see them, a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and types of microorganisms are at work in the world. Most can be classified as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, or fungi, and within each of these categories are species that can be helpful, harmful, or neutral to humans. All people are hosts to microorganisms, which colonize our bodies, forming what is called our microbiome. In fact, in a healthy adult, microbial cells are estimated to outnumber human cells ten to one. Scientists have been working on a project called The Human Microbiome Project which has created a “map” of this biome by studying and recording the microbes in healthy people. Humans aren’t the only ones with microbiomes either. In fact, cows must rely on the microbes in their stomachs to digest their food—they can’t do it alone!

When people get together, the microorganisms that live on them may spread. This becomes a problem when we share germs that cause sickness. We don’t even have to touch each other to trade germs, it can be as simple as using the door knob or picking up a piece of paper that someone sneezed near. People can also pick up germs from other places like food and soil. In most cases, people won’t even notice that there are new germs on their hands or even in their mouths. But sometimes, there are “bad guys” that can get past our immune system and make us sick. The goal of handwashing and other forms of good hygiene practices, like cleaning and disinfecting shared desk surfaces, carefully handling food, and covering your mouth when you sneeze, is to prevent the bad germs from getting into your system and making you sick.

Bacteria are everywhere, including our water supplies. Water supplies in the United States are tested and treated regularly, so we can normally drink water without concern. However, waterborne diseases are common in many other parts of the world where water is not tested and treated. Many deaths in developing countries are caused by diarrhea and related dehydration. Poor sanitation contributes to the spread of bacterial disease, such as cholera, food poisoning, and shigella (shigellosis).

Grocery stores and restaurants in the United States must follow many health standards concerning food safety. They are responsible for providing us with high quality, safe food. Health inspectors routinely inspect establishments that make and sell food to make sure they are following the guidelines. If health inspectors find that a business is not, they can penalize them by closing the business for a specific amount of time or perhaps indefinitely. Eighty-five percent of the cases of food-borne illness caused by bacteria can be avoided with proper food handling. Keys to food safety are washing hands, checking expiration dates, washing surfaces and utensils with hot, soapy water, refrigeration and freezing, rinsing fruits and vegetables, and storing foods in proper places.

In the United States, we are fortunate to have a government that makes food safety a priority. In some countries, food may be produced or imported, but it is spoiled by pests or microorganisms due to poor storage. Pests (insects and rodents) and microorganisms (bacteria, mold, yeast) are the two chief causes of food spoilage. Food must be transported, stored, and prepared correctly to ensure that it does not spoil or grow disease-causing bacteria.

All food will spoil if it is not preserved in some way. Some foods such as nuts and grains can be stored for a long time without spoiling. Other foods such as bread and milk must be consumed quickly. Foods can be preserved in many ways. Canning, freezing, and dehydrating are just a few methods. Spoilage may occur before there is a change in taste or odor. Therefore, consumers should read expiration dates before eating food products bought from grocery stores.

Engage

- Ask for a volunteer, and then invite the volunteer to take a drink from either of two glasses of water. Tell the students that you spit into one glass before class. Discuss the responses. Why wouldn't you want to drink water someone else had spit in? Make the point that disease-causing organisms are found all around us, even in our water.

- Continue the exploration by indicating that the class is going to play a “kissing game.” Distribute the pre-prepared cups of water to each member of the class. (Prior to class time, add 1/8 teaspoon of ammonia or lye to two of the glasses of water. CAUTION: Warn students to not taste any of the samples.) Each student should have a cup of water.

- Indicate that you are going to exchange water from the cups (“kiss”). The procedure is to allow someone to pour some water from their glass into yours. For each amount added, each individual must pour this amount into another person’s glass. Continue this exchange for three minutes.

- After the water exchange, indicate that two of the cups contained germs (represented by ammonia or lye). As with most microorganisms these germs are not easily seen, but they can be detected with a chemical indicator. Speculate on how far you think the germs were spread during the three minutes.

- Add a few drops of phenolphthalein to each glass. If the germ (ammonia or lye) is present, the water will change color. Those with colored water will have been infected.

- Discuss the results. Explain to students that in the following activities, they will learn more about disease-causing microorgansims, how to avoid getting sick, and how microorganisms spoil food.

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: What is My Diagnosis?

Indicate that some class members have exhibited some alarming symptoms or role play with students some “make believe” symptoms you are having. Let them know that you have reason to believe that some microorganisms caused the diseases.

Indicate that some class members have exhibited some alarming symptoms or role play with students some “make believe” symptoms you are having. Let them know that you have reason to believe that some microorganisms caused the diseases.- Form the class into seven cooperative learning groups. Distribute one Symptoms Card to each group and the Waterborne Disease Analysis Key to each student. NOTE: If students have not previously used dichotomous keys, acquaint them with procedures before continuing.

- Have a reporter from each group share their group’s Symptoms Card information with the entire class. Each group should then use this information to key the disease. Do this for all seven Symptoms Cards.

- Optional: Extend this activity by challenging your students to design a "Get a Clue, Guess My Microbe" riddle:

- Assign each student a disease caused by a microbe and ask them to investigate their microbe/disease by using the internet or other library resources.

- Instruct students to keep the identity of their assigned microbe/disease secret and write a series of clues based on their research.

- Ask students to read their clues out loud to the class and see if the class can guess the microbe/disease. If the assigned microbes/diseases are unfamiliar to students, you may wish to provide a bank of options for them to guess from.

- Suggested diseases for further research: botulism, campylobacteriosis, listeriosis, C. perfringens, salmonellosis, shigellosis, staphylococcal, boils, gonorrhea, meningitis, pneumonia, scarlet fever, strep throat, anthrax, diphtheria, plague, tetanus, typhoid fever, cholera, syphilis, African sleeping sickness, malaria

Activity 2: A Germ of Truth

- Talk with the students about where microorganisms can be found, how they spread, and how their spread can be prevented. Remind them that not all microbes are harmful. Some are harmless and others are even helpful. Share the Are you Petri-fied of Germs? article.

- Use this activity to show students the importance of washing hands with soap and warm water:

- Apply cooking spray or vegetable oil to each student’s fingers.

- Sprinkle cinnamon on the palms, backs, and in-between each student’s

- hands. The cinnamon represents germs that get on our hands.

- Try to get rid of the cinnamon using only cold water.

- Try to get rid of the cinnamon using soap and cold water.

- Try to get rid of the cinnamon using soap and warm water. The cinnamon “germs” will rinse right off the student’s hands and into the sink.

- Ask the students why the cinnamon stayed on their hands until they used soap and warm water. How is this similar to washing germs off of our hands? How is it different? Is it important to use soap and warm water for handwashing?

- Have students pair up and give each pair a copy of the A Germ of Truth handout. (You may also choose to project this handout.)

- Inform students that the handout contains excerpts and graphics from different types of literature. Ask students to identify each item as “fiction” or “nonfiction” on the activity sheet.

- Have students use the excerpts to create a one-page fact sheet on germs. If you wish, they can supplement their fact sheet with other research materials.

- Have a discussion about different writing styles and then pose the question: can we still learn facts from fiction? How do you know when a fictitious story is using facts?

Activity 3: Cultivating an Understanding of Microbes

Like all living organisms, microbes need food sources to survive. Some microorganisms even like the same foods humans do! With this experiment, you will be able to “cultivate” colonies of microbes that students can observe while also highlighting the importance of good hygiene practices.

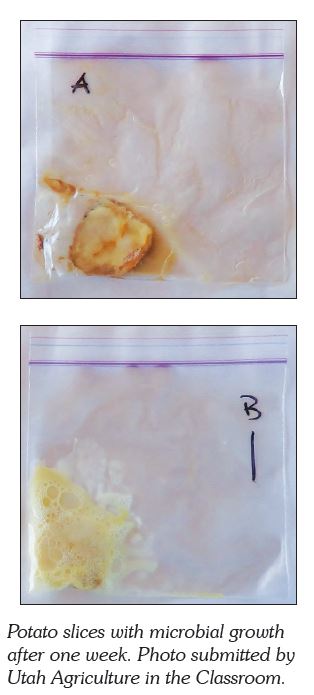

- Prepare the potatoes before beginning this activity. Peel them deeply, then cut them into round, 1/4-inch slices. Microwave the slices for 1-2 minutes, until just soft. Note: Because potatoes are grown in soil, this experiment will not be sterile. You may want to introduce students to the concepts of safe food handling practices that farmers and grocery stores observe, pointing out that, while the foods are kept safe, there is no way to make them sterile. By cooking the potato and limiting the amount of contaminants that touch the potato before the experiment starts, you will see greater differences later on.

- Have students pair up, and give each group two resealable plastic bags. Students should label the bags A and B. Explain that Bag A will be for the handwashing test and Bag B will be for the hand sanitizer test. You may want display this information or write it on the board to help students avoid confusion. Students may decide between themselves who will perform Test A (handwashing) and who will perform Test B (hand sanitizer).

- Ask all Test A students to wash their hands thoroughly. Then as they return to their desks have them take a potato slice. Without touching anything else, students should rub the potato between their hands and then place it into Bag A, sealing the bag closed.

- Next, Test B students should clean their hands with hand sanitizer. They will also take a potato slice, rub it all over their hands, and seal it into Bag B.

- Microorganisms will grow best if the potato slice is very moist. If the potato slices seem dry, you may have students add a little moisture using either an eye dropper or a spray bottle.

- Collect the bags and place them in an out-of-the-way spot (dark, warm conditions will yield the quickest results) for one or two days. Microorganisms will soon be apparent. Note: right after potatoes are peeled and cut, they may discolor and turn brownish. This is normal, but be sure to tell students that this is not due to microorganisms (it is a process of oxidation) and to watch for other signs of microbes that will appear over the course of a few days.

- Once students have completed the experiment procedures, have them answer the following questions in a science journal:

- What is this experiment designed to test?

- What do you predict will happen in each of the bags?

- What are the variables in this experiment? What could be changed to influence the outcome?

- When the microorganisms begin to appear, return the samples to each group and have them record their observations. Warn students: DO NOT OPEN THE BAGS. The bags are contaminated with microorganisms that could make people sick and will stink up the classroom at the very least. Students should only observe the samples through the plastic.

- Have each student add to their science journal by sketching and describing their observations. Be sure that any students that handle the bags wash their hands afterward.

- Collect the samples and wait one or two more days, then repeat step 8. Results will typically show that handwashing is more effective at reducing microbial growth; however, it is important to note that, since microorganisms are everywhere, contamination can cause samples to spoil even when you are trying to maintain high standards of cleanliness. Having results that vary from what is expected does not equal failure; it is just a reminder that microorganisms are a daily part of life and that the best thing students can do to avoid getting sick is to wash their hands before they touch anything that goes into their mouths and before preparing food.

- At the end of the experiment, have students consider the following questions.

- Which potato slice appeared to have the most microbial growth when you examined them the first time? What about the second time?

- Can you see differences between the types of microorganisms that are growing on the potatoes?

- What did this test teach you about microorganisms? (They are everywhere, but you don’t have to be afraid if you take simple precautions.)

- What can we learn about preventing the spread of microorganisms? (Handwashing is the more effective method.)

- What are some places that microorganisms live?

- Since farmers harvest their potatoes in the fall and store them for use during the rest of the year, what can be done to keep them from spoiling? (Store them in a cool, dry location)

Elaborate

-

Explore some of the positive impacts microorganisms have on our food by sharing the TED-Ed video The Beneficial Bacteria That Make Delicious Food (4:39 min) with your students.

-

Looking for more motivation to get kids washing their hands? Watch the fun, 7-minute video Protect! Don't Infect: Germ Wars. This light, understandable seven-minute video shows how germs are spread from person to person... from the germ’s point of view!

-

Because cooked potatoes are an excellent food source for microorganisms, they can be used as the basis for many more microbial experiments:

- Where do microorganisms grow? Try rubbing the slices on light switches, tissue boxes, the floor, etc. and comparing them with the results from the experiment in Activity 3 of this lesson plan.

- What keeps microorganisms from growing? Treat slices with vinegar, salt water, sugar water, and rubbing alcohol to explore what types of preservatives can keep microorganisms from growing.

- What do microorganisms like? Try subjecting the potato slices to different conditions: sunlight, artificial light, and dark; hot and cold; moist and dry. See what makes microorganisms grow fastest and slowest.

Evaluate

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key concepts:

- Microorganisms are everywhere, and they affect our lives in many ways.

- Many microorgansims, like bacteria, are made of one, single cell.

- Some microorganisms can make us sick, but simple precautions greatly minimize the risk.

- Washing your hands before eating or preparing food is one of the easiest ways to prevent microbes from making you sick.

Recommended Companion Resources

- Animated Life: Seeing the Invisible

- Beef Blasters

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: How Fast Will They Grow?

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Mighty Microbes

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Operation Kitchen Impossible

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Playing it Safe

- Germ Stories

- Glo Germ Set

- Show Them The Germs!